In Australia, the rose-breasted cockatoo is known as the "galah." It can be found in the wild in the multi-thousands. For bird watchers and visitors, the galah is truly a fantastic sight to see. They are most often seen in groups, both small and large. When seen in the hundreds, whether in trees or flying in the air, it becomes a memorable experience.

For the Australian aviculturist, the galah is not a prized bird. Because of their great numbers in the wild where they are often considered an agricultural pest by some of the farmers, this cockatoo is worth almost nothing in captivity. If kept at all, it is usually as a pet.

The value of the galah or rose-breasted cockatoo is well illustrated by a personal experience I observed while I was in a Sidney pet store. A twelve-year-old boy came into the shop with a tame galah that was kept in a 12" x 14" x 18" cage. He wanted to sell it to the manager of the pet store but was turned down. After some discussion, the boy traded his tame galah for one grey cockatiel and one female red-rumped parakeet. Although this was an astonishing transaction to me, the young boy seemed very elated with the trade.

When discussing the situation with the boy (who at first seemed reluctant to talk), he related that he had removed the galah (he referred to it as a "cockie") from a nest in the wild, hand-reared it and then had become tired of it.

How different this cockatoo is to the American aviculturist and pet owner! Because it has not been exported from Australia since the mid 1950s, when exportation of all native wildlife was completely banned, the rose-breasted cockatoo is not found in large numbers as are many of the white cockatoos from Indonesia.

In the wild the rose-breasted cockatoo is found only in Australia and taxonomists have placed it in its monotype genus, eolophus. It can be found throughout Australia, but it prefers open grasslands and Savannah woodlands. Being so common it can be found in areas inhabited by humans which is why it is easily observed by tourists visiting in and around the big cities.

The rose-breasted cockatoo is very tolerant to the great climate variations of Australia. It survives the severe hot daytime temperatures of the deserts that can drop over 30 degrees during the night hours. In captivity when sheltered from any wind, this cockatoo can easily withstand temperatures that fall below freezing at night.

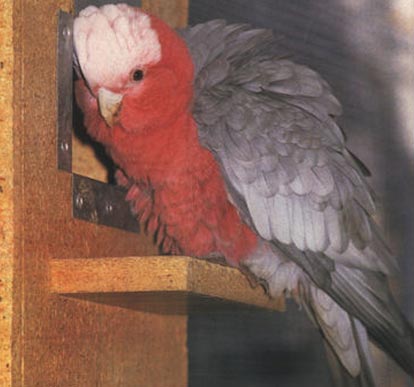

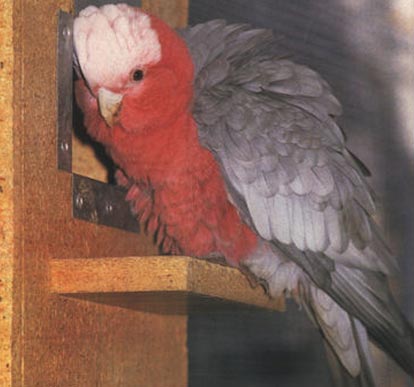

Coloration

Color is a big reason for the popularity of this medium-sized cockatoo. With its rose-pink chest, under parts, neck and face contrasting its grey wings and tail, the rose-breasted cockatoo is, indeed, a striking bird.

There are two shades of the rose-pink coloration found in this cockatoo. Birds from eastern and northern Australia have a more brilliant shade of rose, compared to the subspecies found in western Australia. The great majority of rose-breasted cockatoos found in captivity are the paler version. In my opinion, this bird just shows more grey in the scalloping of the pink chest and frontal crest.

The dark pink subspecies has a very whitish frontal crest, and the periophthalmic ring (naked skin directly around the eye) is distinctively red compared to the pale whitish grey eye ring on the paler subspecies. This whitish grey eye ring is only tinged with pink coloration. Although seldom seen, the true subspecies having the deep red coloration is quite distinctive. Males appear even darker then the females and are more common. Very dark red females are quite scarce. Having had the privilege of breeding one of these dark red pairs, I have been able to follow some of their offspring to determine if they kept the deeper red coloration of their parents. They do, indeed, retain the dark red coloration of their parents, which becomes very evident after their first molt.

The great majority of adult rose-breasted cockatoos can be sexed by their eye coloration and the intensity of the red or pink coloration of the naked skin around the eye.

Adult males have a darker eye coloration compared to females. The iris of the male is dark brown (appearing almost black from a distance), while the iris of the female ranges from light brown to pinkish red. The naked periophthalmic ring is usually thicker and darker in its pigmentation in males. Sexing by eye coloration, however, is not 100 percent accurate in rose-breasted cockatoos. An importer of rose-breasted cockatoos from Europe in the 1980s gave an estimation of five percent of these birds that could be mistaken for the wrong sex. He recommended that any questionable bird be sexed surgically or by chromosome sexing.

In the fifteen years that I have kept rose-breasted cockatoos, only one pair could not be sexed by eye color. Both the male and the female of this pair had very light brown eyes. On every occasion when visitors observed this pair, they were quick to tell me that I had two females in the flight. My reply was that these two light-eyed birds produced babies.

BREEDING

In the wild, pairs of rose-breasted cockatoos separate themselves from the flock in the early spring to begin their nesting season. Although breeding pairs can be relatively close to each other they still will defend their own nesting tree and the immediate surrounding area.

In captivity, the rose-breasted cockatoo can be placed in breeding cages or flights while the pairs can visually observe each other. Although colony breeding in a very large flight has been tried with this cockatoo its success has been very low. Usually, the alpha pairs nest successfully while the other pairs are disrupted sometime during their nesting season. Rose-breasted cockatoos can even be kept in adjoining cages or flights, but it is best that a double layer of wire (separated by two inches) be used between them. This is to keep any toes from being bitten through the wire. If adjoining flights are used, it is highly advisable to visually partition the area surrounding the nests. The nests can be defended quite vigorously, and partitioning keeps any pair from seeing another pair entering and exiting their own nest. Most aviculturists, however, do place another non-related pair of birds between their rose-breasted pairs. Any white cockatoo pair should be treated differently then the rose-breasted cockatoo. White cockatoos should always be visually partitioned completely from any pairs of the same species and, often times, from similar species. Most aviculturists keep pairs of Moluccans, Umbrellas and any Sulpher-crested cockatoos well away from each other. Otherwise, aggressive and defensive behaviors on the part of the males may occur, which may result in transferred aggression to their mates. Often, the female may be maimed quite severely by the male.

HOUSING

Rose-breasted cockatoos can be bred in a variety of cage and flight sizes. Because the rose-breasted cockatoo is prone to becoming very overweight, it is very important to give this cockatoo enough space for exercise. Housing for rose-breasted cockatoos ranges from 12 to 30 ft flights that reach the ground floor, to 8-foot long suspended cages. Almost all of the old-time aviculturists bred them in long flights that enabled the birds to fly from perch to perch or from the ground up to the perch. This certainly gave the birds good flying exercise. Rose-breasted cockatoos love to be on the ground and can be observed there in the early morning sun or in the late afternoon. If your birds are kept in a flight, place a large rock (9 to 12 inches in diameter) or group of rocks on the ground in the middle of the flight. The cockatoos enjoy perching on these rocks after grubbing in the ground.

When breeding rose-breasted cockatoos in smaller suspended cages, limit the amount of food you feed to each pair to keep them trim.

NESTS AND NESTING MATERIAL

Rose-breasted cockatoos nest very early in the spring. In both the wild and in captivity, the rose-breasted cockatoo is one of the very first cockatoos to go to nest. Australia is in the southern hemisphere, and rose-breasted cockatoos begin nesting in the months of August and September, which is our Autumn. In the United States, captive rose-breasts breed in our Spring and often lay eggs in the month of February and certainly in March.

Wooden vertical nest boxes measuring 12 x 12 x 24 inches to 36 inches are commonly used for rose-breasted cockatoos. It is best to use thick wooden planks (modified two inch thickness) for the size of the nest to aid in insulating the temperature around the eggs or young. Rose-breasted cockatoos are certainly not the chewers that many of the other cockatoo species are. Using a practice I have implemented for many years, I have always placed two and often three nest boxes in with each pair of cockatoos no matter what the species. Each nest is placed on opposite walls of the cage or flight so that the birds will have a choice of location. Usually they will choose only one nest, but, on some occasions, they will switch to the other nest box. This can even happen during one breeding season where each succeeding clutch of eggs is laid in a different nest.

Speaking with several Australian biologists and aviculturists, I learned that many of the natural nests used by rose-breasted cockatoos in the wild can have an inside diameter as little as six inches. The cockatoos easily rear four babies within this tight space. Almost all of the nests used in the wild are found in Eucalyptus trees.

I decided to fashion a nest in captivity to match those found in the wild. I found a Eucalyptus grove in California that was to be cut down for a housing project and acquired several Eucalyptus logs measuring between 14 and 26 inches in diameter. These logs were then cut in 3-ft. lengths, and the tree cutter was hired to split them evenly down the center. The tree cutter then cut a lengthwise v-cut out of the center of each half log. I then bound the two halves back together and kept both ends in thick wood. A five-inch nest entrance was cut near the top by a narrow chainsaw blade and likewise, a five-inch inspection door was cut near the bottom. The inspection door plug could then be replaced and securely attached. The entire Eucalyptus nest was made light-tight by cutting the vertical cuts with a narrow sheet of sheet metal. The inside diameter of these Eucalyptus nests range from six to eight inches and these boxes were chosen over all of the manmade wooden vertical nests by every species of cockatoo I offered them to. Although they were heavy, the success resulting from these Eucalyptus nests far outweighed the problem of lifting them in place.

Because of the thickness of the walls of these Eucalyptus logs, the temperatures within the nest was quite different from outside temperatures that were of an extreme nature. In very hot weather, the inside temperatures would often be 15 degrees Fahrenheit cooler (or more) than the outside temperatures. In cold weather, any incubating or brooding adult cockatoo will keep the nest chamber heated, which keeps the eggs or young from chilling, even when the adult leaves the nest for a short period of time. The heavy insulated nest keeps it from chilling rapidly. Rose-breasted cockatoos often nest in very cold weather, and I have had young babies in a Eucalyptus nest when there is snow outside.

Rose-breasted cockatoos are one of the very few cockatoos that bring nesting material into the nesting chamber. Most cockatoos use the woodchips originally found within the nest. Rose-breasted cockatoos will bring in fresh Eucalyptus leaves to build their nests. When available, fresh eucalyptus leaves should be supplied to any pairs of rose breasts, since it really stimulates their courtship and nesting behavior. I begin giving my rose breasts fresh limbs of eucalyptus on a regular basis around Christmas time and continue giving them a fresh supply every week during the complete nesting season.

The late Ken McConnell was one of the most successful breeders of rose-breasted cockatoos. Many of his rose-breasted cockatoo flights were 20 to 30 feet long and had grass planted in the ground floor. When I visited him in 1983, he showed me a rose breast nest that contained five fertile eggs. The parent birds had built a beautiful nest with eucalyptus leaves that cushioned the eggs. This pair had placed a top layer of individual eucalyptus leaves lengthwise around the eggs, with the leaf ends facing the eggs. These leaves had formed a star-like shape around the eggs. Most pairs are not this particular.

Long, narrow eucalyptus leaves are much preferred by rose breasts over the rounded leaves similar to the silver dollar eucalyptus tree. Rose-breasted cockatoos lay an average of three to five eggs, and the incubation begins with the second or third egg. Because of this, the babies hatched in sequence and are of staggered sizes.

Newly hatched rose-breasted cockatoos are covered with a light pink down. The young babies grow rapidly; in the wild, it is important to fledge as soon as possible due to the possible climatic changes and the availability of seeding grasses and other food items.

Many aviculturists remove rose-breasted cockatoo eggs as soon as they are laid and place them in artificial incubators. This strategy results in many more eggs being produced within the breeding season than by allowing the parents to incubate and rear their own young to an age of ten days before removing them for handfeeding.

Babies that have been partially parent-reared are easier to handfeed and have fewer bacterial problems than those being handreared from day one. Having personally reared rose breast babies both from the incubator and from the parent birds, I have found that those babies that have been partially fed by the parents are more developed physically at the same age. At five weeks of age, the baby from the parent's nest has more developed feathers. Although it can be done, it is difficult to match the parent birds when handfeeding day one babies.

Rose-breasted cockatoos can reproduce at one year of age, but I believe this is too early, since they are not completely mature. I have always doubted this early age of breeding until I sold a four-month old female to a breeder friend who had lost the female of a producing pair of rose breasts. The following year, the male, who was experienced, produced fertile eggs with my young female when she was 12 months of age. I believe this happened only because the male was a previous producer. He had taught and led the young female through the nesting period. I also believe that a pair of birds both being only one year of age would have a low probability of producing eggs, since they would have no experience.

Handfed rose-breasted cockatoos make good future breeding stock. They are very different than the cuddly handfed Moluccan and Umbrellas cockatoos. The rose-breasted cockatoo has a very outgoing personality, and it is this trait that makes it somewhat independent. This trait also aids in making good breeders later on. Even so, an isolated, human imprinted rose-breast baby is a poor candidate for being an excellent breeder in comparison to one that has socialized with other rose breasts and with other birds.

Keeping rose-breasted cockatoos in a trim and healthy condition is the key to their successful reproduction. In captivity, the rose-breasted cockatoo commonly develops fatty tumors or lymphomas. These tumors can hinder reproduction and are a great cause for infertility.

Rose-breasted cockatoos, unlike most other cockatoo species, are prone to obesity. They should be given a nutritionally balanced diet that lacks most types of foods that contain a large percentage of fat. Eliminating high fat content foods and giving these cockatoos enough space to adequately exercise are the two main ways to reduce the chance for fatty tumors. Dry seeds, such as sunflower and safflower, should not be offered to these cockatoos. Even dry parakeet seed can make them overweight. For several years, we gave our rose breasts vegetables (corn, peas, carrots and beans), along with a teaspoon of dry parakeet seed. The birds still had great difficulty flying from the ground to their perches.

We have now eliminated all dry seed completely and will even limit the total amount of vegetable food given per pair. Approximately one-half cup of vegetable types of foods ("soak and cook"), of which forty percent is made up of a pelletted or extruded diet, is given per pair per day. This, along with a twenty-two foot flight, keeps our pairs of rose-breasted cockatoos in trim condition. They fly swiftly from perch to perch, instead of struggling to reach them. Our production has risen many times since this dietary program has been in place. A very small amount of vitamins and calcium is added to the soak and cook. Additional foods are added, including parakeet seed, when babies are in the nest. The parents gain weight during this time, so we reduce their weight in the off season.

Rose-breasted cockatoos enjoy the rain and often hang upside down from the tops of their cages to catch the raindrops. A sprinkler system placed above their cages, not only cools them down but offers these birds an enjoyable time playing in the mist.